Please don't touch the coral: shelling in Zanzibar

by Janet T. Sawyer

Photographs courtesy of Africa Travel Resource

Photographs courtesy of Africa Travel Resource

As a shell collector I have a dream; I have a dream that I am walking along a sandy beach, with the warm sun shining above, an azure sea lapping peacefully beside me, a soft breeze sighing through the supple palms and a distant fishing boat with its sails at rest being hauled joyfully to the shore. I have a dream in which I step on to that beach and see nestled in golden sand, a huge specimen sea shell. I reach out my hand to pick it up, and the shell vanishes; I am lying in bed at home. Well, I dreamt that dream during my holiday in Zanzibar, and although I have long since journeyed home, I still have not yet woken up!

Fisherman's Resort, my hotel in Zanzibar, was beautifully situated among palm trees on a coral-fringed bay with the biggest swimming pool on the island. I had arrived at the hotel amid a tropical thunderstorm which continued for two days and it was not until late on the second afternoon that I stepped on to the beach beside the hotel. At once two security guards appeared and I assumed they were going to stop me from shell-collecting. Not at all, they were merely anxious that I should not go beyond the hotel's boundary signs which marked the limits of their jurisdiction. In fact the local inhabitants regarded shell-collecting outside the protected area as competing for living mollusca as a food source and as a supplement to their incomes.

I walked along to a fishing boat drawn up on the sand, thinking that the crew might have thrown out some shells which had become entangled in their nets or lobster pots. This thought paid off because I immediately found a good specimen of Chicoreus ramosus, L. 1758. Another good find was a specimen of Strombus decorus masirensis Moolenbeek and Decker, 1993. I subsequently identified this specimen using the book Sea Shells of Eastern Arabia published by Motivate and edited by BSCC elder statesman Peter Dance. I found this work extremely relevant to Zanzibar for a curious historical reason. Apart from dug-out canoes, paddled across the strait from the nearby mainland, the first ships to reach Zanzibar Island were Persians sailing from Shiraz as early as the 10th century, whom the winds and currents brought to these shores. In later centuries Arab traders came from all parts of the Middle East and during the 18th and 19th centuries, Zanzibar was actually united with the Sultanate of Oman. If the early boatmen reached the shores of Zanzibar by setting out from the Arabian Peninsula with their imperfect methods of seamanship and navigation, might one not suppose that several specimens of mollusc had managed to accomplish the same journey?

|

Chicoreus ramosus L, 1758

|

Conus marmoreus Linné, 1758

|

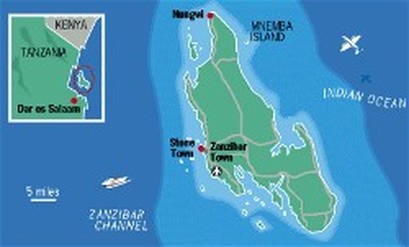

The island of Zanzibar is 50 miles long from north to south and 24 miles wide. Its population is half a million, with a further 300,000 living on the neighbouring island of Pemba. The two islands together form the state of Zanzibar which since the revolution of 1964 has been joined together with Tanganyika to create the federation of Tanzania. Although Zanzibar has its own legislature, links with mainland Tanzania and its capital Dar es Salaam are strong. Kiswahili is the national language throughout, although Arabic and English are both spoken in Zanzibar. In the early part of this century the Sultan sought British assistance against German influence from Tanganyika and Zanzibar became a British Protectorate until 1963 when it was granted independence.

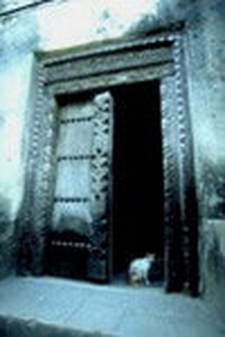

Zanzibar has a long history of involvement in the slave trade. The explorers Livingstone, Stanley, Burton and Speke, who all went to Zanzibar to recruit porters for their expeditions to the African continent, had many a conflict with Arab slave traders in their journeys through Central Africa. In fact David Livingstone campaigned from Zanzibar itself for the slave trade to end and he is much revered there for having succeeded. The beastly business eventually came to an end in 1873, some 65 years after it had been outlawed in the UK. In the capital of Zanzibar, Stone Town, there are two houses where David Livingstone stayed, and in the Cathedral which was constructed on the site of the old slave market, there is a cross made from the tree beneath which Livingstone died. Stone Town also offers to the discerning tourist three palaces, three museums, the underground slave cells, a yard where dhows are under construction and a lively market selling fish, meat, vegetables, spices and fruit, as well as characteristic narrow alleyways and richly-carved doors. Three quarters of the world's cloves come from Zanzibar, although most are grown in Pemba. However, there are shady avenues of mango and fig trees, plantations of cassava and maize, stands of mahogany and palm wood used for making furniture and stretches of mangrove scrub used in the building of boats, making this an island of welcome greenery.

Zanzibar has its own endemic species of leopard and wild cats, as well as the unique Red Colobus Monkey which can be seen at close quarters in the Josani Forest Reserve. The tours scheduled by my tour agency provided me with a "City Tour" of Stone Town and a day trip to the Josani Forest coupled with a "Spices Tour" of several agricultural plantations. However it would not touch the coast at all. I had already contacted the local tourist agency at my hotel run by a splendid African lady called Flora, whilst the thunderstorm was still raging. Flora arranged for me to take a day trip to the northernmost point of the island at Nungwi.

A minibus duly arrived at my hotel at 9.00am and as I was the only person travelling I had the driver and the guide, a mature and very respectable Moslem called Salim, at my complete disposal. First we drove north through the suburbs of Zanzibar Town, past the large fairground where families take their children at weekends, and past several schools with their uniformed pupils, the girls wearing white Islamic headscarves. In Tanzania education is state-subsidised, although the parents have to contribute a certain amount. Classes double up with morning and afternoon sessions for different sets of pupils as they are so short of buildings and equipment. Then we drove along shady avenues of mango trees with small-holdings on either side and small houses made either of mud bricks with palm thatch or of the more modern grey concrete bricks with a tin roof. The plantations grew bananas, coconuts, breadfruit, jackfruit, durian, pineapple, papaya, roseapple, lychees, ginger, cinnamon, peppers, cloves, vanilla and many other exotic tropical products. I now know what a nutmeg looks like when it's growing, the scarlet nut being hidden inside a pithy peach-like fruit.

Suddenly the road leaves behind the well-watered forest and emerges on to the drier northern end of the island where the only crops which the thin soil atop the infertile coral rock base can bear are small fields of cassava and a scattering of fig and baobab trees. We reached the large village of Nungwi after wending our way between the potholes of a dirt road for the last 20km. Nungwi is a village completely lacking in streets. Vehicles simply drive around the individual houses. This leads to some hilarious encounters with domestic livestock and surprised villagers, especially when our driver lost his way.

I was taken to inspect a number of beach locations till I communicated as tactfully as possible that I did not wish to swim but rather to look for shells. Salim said he knew just the place and indeed when we arrived there were fishing boats drawn up on the sand which was marked by several hopeful-looking strand lines. I jumped out of the vehicle, plastic collecting bag at the ready, and there at my feet was a huge pile of shells – Conus betulinus L., 1758 for the most part, with some Lambis, Chicoreus ramosus, Conus virgo and the occasional Cypraea. Knowing that Conus betulinus was used as live bait by the fisherman in their lobster pots, I assumed that this pile had been thrown aside after the animal inside had been consumed by the trapped lobster, so I started to pick up a few specimens.

"Hey!" said a voice behind me in Swahili. "That's my stock you're taking!" He was the local shell dealer. Salim showed him the contents of my bag and asked him how much he would charge. "One thousand shillings," he replied. I quickly handed over the Tanzanian equivalent of £1 sterling and promised the dealer as much business again on my return. Although one is not supposed to encourage the trade in shells, I was pretty sure this was purely local material supplied by the incoming fisherman. In fact the dealer wanted only 300 shillings for each "clean specimen" and could not understand why I should be interested in the "dirty" ones from the beach. I selected two cones and a Cypraea which would be easy to carry and asked for a Malea pomum L., 1758 as a make-weight. I duly handed over another 1,000 shilling note and turned away, only to have the dealer run after me and pop a perfect Harpa harpa L., 1758 into my bag. I found the people of Zanzibar generous and courteous to a fault, often apologising for errors of politeness which we have forgotten to observe in our modern selfishness.

In the meantime I had been strolling along the beach with my guide Salim. I was the first shell-collector he had met and he was eager to learn the rudiments in order, no doubt, to offer a similar service to other tourists in the future. Whilst I retrieved perfect specimens of Cypraea caurica L., 1758, Conus augur Lightfoot, 1786, Bulla ampulla L. 1758 and Codakia punctata L., 1758 from beneath my feet, I gave Salim a few hints on what to look for in the quality of a collectable shell and taught him some of the common names. But how do you explain the meaning of Conus virgo to a very upright Moslem? At the end of the beach there was an aquarium stocked with Hawksbill Turtle, a species threatened with extinction, along with several species of fish, some of which behaved like frenzied piranhas when their keeper threw them the innards from a marlin.

Then it was back to the minibus, passing a Moslem funeral on our way to the village with the relatives sitting around the heaped-up grave in a forest grove. We drove between even worse potholes to the Ras Nungwi Beach Hotel where I had lunch of delicious king fish (marlin) and afterwards descended to the sands to look for more shells. This end of the beach was even better than the part where the boats were drawn up. I picked up several beautiful specimens of Cypraea helvola L., 1758, Conus ebraeus L., 1758, several species of nerite and a variety of bivalves, Trachycardium flavum L., 1758 and T. elongatum Bruguiere, 1789 being among the most attractive. I also collected a fine specimen of Volema paradisiaca Roding, 1798. It contained a large hermit crab which I tried every ruse to remove and install in alternative accommodation, but had to give up in the end. I left it on my balcony overnight and in the morning it had vanished.

My scheduled tour of the spice plantations and the visit to the Red Colobus Monkeys in the Josani Forest had now taken place. This time I had several companions including a farmer from Colchester called James who had just completed a sponsored climb of Mount Kilimanjaro at 5895m (19,340ft) in aid of S.C.O.P.E. A day or two later I received a pre-breakfast telephone call from my tour guide; would I like to go on another trip as James wanted to swim with the dolphins off the southern coast of the island and it would cost only half as much if I would share the trip. I enquired what I should do whilst James was pursuing the dolphins since I do not swim. "Oh, there's a beach nearby and a restaurant where we will have lunch." I agreed to take part, much relieved at having been saved the embarrassment of confessing my trip with the opposition had they suggested a tour to the north coast instead.

The route south provided a mirror image of the route north. My hotel was already situated south of the capital and just past the airport, so we entered immediately the avenues of mango trees and small-holdings, only to emerge once again into a drier area where the road wound among the baobabs and straggling cassava plantations. Soon we were dodging a jigsaw-puzzle of potholes until we reached the sea at a small village called Kizimkazi. Here the local population seemed to have foregathered around a large concrete shelter for the fishermen which bore the panda badge of the Worldwide Fund for Nature. Presumably that organisation had sponsored its construction. The fishing fleet was making its way ashore and several boats were being dragged up on the sand – their lateen sails flapped idly in the breeze. Cleaning of the catch took place on the spot and the fish were obviously intended for local consumption. I recognised a Red Snapper as a small boy ran past holding it aloft in delight.

Then I walked on to the beach and stared down at the strand line in sheer disbelief. There, scarcely a yard in front of my feet, was a large and perfect specimen of Lambis chiragra f. arthritica Roding, 1798; a few yards further on I found perfect specimens of L. lambis L., 1578 and L. crocata Link, 1807. Three Lambis species in the first five minutes; surely I must be dreaming? But the dream continued with fine specimens of Conus betulinus L., 1758, the rare yellow form of Vasum rhinoceros Gmelin, 1791, a large and colourful Strombus lentiginosus L., 1758, large quantaties of S. gibberulus gibberulus L., 1758 and S. decorus decorus Roding, 1798, and a large specimen of Phasianella variegata Lamarck, 1822. Among the bivalves there were pairs of Codakia tigerina L., 1758 and C. punctata L., 1758 and valves of Tellina staurella Lamarck, 1818.

I soon realised that I had chanced upon a virgin beach where none had collected before me and where it had not occurred to the local inhabitants to commercialise the treasures tossed up on their sands. I was carrying my camera, handbag and other equipment safely concealed from public gaze in a large beach bag. As soon as I had filled one plastic bag with shells I tucked it quickly and surreptitiously out of sight in the beach bag and pulled out an empty bag instead. Thus when I reached the villagers on my return journey I had only few shells in a transparent bag. Nobody pestered me till I happened to take a photograph of the beach which included one of the many small children and his father came up asking for money. I suggested he should send his son to school where he would learn to read and write and could get a job when he left so that he would not need to beg! I think the message went home for the father moved away. Later at the restaurant where we had lunch I saw a strongbox asking for donations to a "School development project" and I was able to make a contribution which went some way towards compensating the villagers for the beautiful shells I had been able to find.

James reached the restaurant at the same time as I reluctantly left the beach. He had had a splendid morning diving from a boat and swimming alongside dolphins who had become accustomed to meeting tourists. His guide brought me a large cone, C. terebra thomasi Sowerby, 1881, but seeing that the creature inside was alive I asked him to return it to the sea, since I make it a rule never to take live material for reasons of conservation, as well as of practicality, during my foreign tours.

Similarly, when I came across a specimen of Achatina reticulata Pfeiffer, 1845, a huge creature with a shell about 7in long and a body to match, which had accidentally fallen from the low cliff, I captured it with my camera, which alas was fitted only with a 28mm lens at the time.

I had an opportunity of explaining my collecting policy whilst taking down the names of the shells on display at the Natural History Museum in Stone Town. I was approached by a tourist guide accompanying a couple who wished to collect some shells and who wondered whether it was forbidden. I informed them it was my understanding that collecting was discouraged without being actually forbidden. My own collection was for the purposes of scientific study, I emphasised (the residents of Kizimakazi when similarly informed had assumed I was a representative of WWFN!). However, for conservation reasons I avoided taking live material and of course I wouldn't touch the coral which the islanders regard as a part of their island and a source of their livelihood. The guide nodded approvingly and I felt I had struck the right balance between the developed and the developing worlds.

A full list of my finds at the three locations is appended to this article. Once again my grateful thanks are due to Mr Kevin Brown for his assistance with the identifications and for the loan of his book The Sea Shells of Dar es Salaam by J.F. Spry (1964), published in two volumes in Tanzania. My other chief source of knowledge was, as usual, the invaluable Compendium of Sea Shells by Dr Tucker Abbott and S. Peter Dance as well as Sea Shells of Eastern Arabia by S. Peter Dance.

This article by Janet Sawyer was first published in our magazine Pallidula in October 1999.

Species list

Cellana rota Gmelin, 1791

Trochus maculatus L., 1758

Phasianella variegata Lamarck, 1822

Nerita albicilla L., 1758

N. chamaeleon L., 1758

N. planospira Anton, 1839

N. plicata L., 1758

N. undata L., 1758

Terebralia palustris L., 1767

Cerithium nodulosum Brugiere, 1792

C. caeruleum Sowerby, 1855

C. columna Sowerby, 1834

Calyptraea pellucida Reeve, 1859

Malluvium lissum Smith, 1894

Strombus urceus L., 1758

S. mutabilis Swainson, 1821

S. lentiginosus L., 1758

S. decorus decorus Roding, 1798

S. decorus masirensis Moolenbeek & Dekker, 1993

S. gibberulus gibberulus L., 1758

S. gibberulus albus Morch, 1850

Lambis lambis L., 1758

L. crocata crocata Link, 1807

L. chiragra f. arthritica Roding, 1798

Trivirostra oryza Lamarck, 1811

Cypraea annulus L., 1758

C. carneola L., 1758

C. caurica L., 1758

C. chinensis Gmelin, 1791

C. helvola L., 1758

C. lynx L., 1758

C. moneta L., 1758

C. vitellus L., 1758

C. clandestina passerina Melvill, 1888

Polinices mamilla L., 1758

Natica gualteriana Recluz, 1844

Malea pomum L., 1758

Tonna luteostoma Kuster, 1857

T. perdix L., 1758

Cymatium nicobaricum Roding, 1798

Naquetia triquetra Born, 1778

Chicoreus ramosus L., 1758

Volema paradisiaca Roding, 1798

Nassarius coronatus Bruguiere, 1789

N. distortus A. Adams, 1852

Pleuroploca trapezium L., 1758

Ancilla mauritiana Sowerby, 1830

Vasum rhinoceros Gmelin, 1791

V. turbinellus L., 1758

Harpa harpa L., 1758

Conus namocanus Hwass, 1792

C. augur Lightfoot, 1786

C. betulinus L., 1758

C. chaldeus Roding, 1798

C. coronatus Gmelin, 1791

C. ebraeus L., 1758

C. fulgetrum Sowerby, 1831

C. lividus Hwass, 1972

C. miles L., 1758

C. terebra thomasi Sowerby, 1881

C. tessulatus Born, l778

C. virgo L., 1758

Bulla ampulla L., 1758

Atys cylindricus Hebling, 1779

Melampus castaneus Muhlfield, 1815

Arca naviculularis Bruguiere, 1789

A. avellana Lamarck, 1819

Anadara antiquata L., 1758

A. uropygimelana Bory St Vincent, 1824

Barbatia amygdalumtostum Roding, 1798

B. velata Sowerby, 1843

Glycymeris petunculus L., 1758

Modiolus auriculatus Krauss, 1848

Brachidontes variabilis Krauss, 1848

Servatrina pectinata L., 1767

Pinctada radiata Leach, 1814

P. radiata f. nigra Gould, 1850

P. margaritifera L., 1758

Isognomon isognomon L., 1758

Chlamys senatoria Gmelin, 1791

Spondylus marisrubri Roding, 1798

Striostrea margaritacea Lamarck, 1819

Saccostrea cuccullata Born, 1778

Codakia punctata L., 1758

C. tigerina L., 1758

Ctena bella Conrad, 1837

Lucina victorialis Melvill, 1899

Wallucina erithraea Issel, 1869

Diplodonta genethila Melvill, 1898

Chama reflexa Reeve, 1846

Beguina gubernaculum Reeve, 1843

Bourdotia boschorum Dekker & Goud, 1994

Trachycardium flavum L., 1758

T. elongatum Bruguiere, 1789

Fragum fragum L., 1758

Mactra ovalina Lamarck, 1818

Atactodea glabrata Gmelin, 1791

Tellina staurelia Lamarck, 1818

T. palatum Iredale, 1929

T. claudia Melvil1 & Standen, 1907

Cadella semen Henley, 1845

Circe rugifera Lamarck, 1818

Asaphis violescens Forsskal, 1775

Gafrarium pectinatum L., 1758

G. tumidum Roding, 1798

Donax cuneatus L., 1758

Dosinia alta Dunker, 1848

Cellana rota Gmelin, 1791

Trochus maculatus L., 1758

Phasianella variegata Lamarck, 1822

Nerita albicilla L., 1758

N. chamaeleon L., 1758

N. planospira Anton, 1839

N. plicata L., 1758

N. undata L., 1758

Terebralia palustris L., 1767

Cerithium nodulosum Brugiere, 1792

C. caeruleum Sowerby, 1855

C. columna Sowerby, 1834

Calyptraea pellucida Reeve, 1859

Malluvium lissum Smith, 1894

Strombus urceus L., 1758

S. mutabilis Swainson, 1821

S. lentiginosus L., 1758

S. decorus decorus Roding, 1798

S. decorus masirensis Moolenbeek & Dekker, 1993

S. gibberulus gibberulus L., 1758

S. gibberulus albus Morch, 1850

Lambis lambis L., 1758

L. crocata crocata Link, 1807

L. chiragra f. arthritica Roding, 1798

Trivirostra oryza Lamarck, 1811

Cypraea annulus L., 1758

C. carneola L., 1758

C. caurica L., 1758

C. chinensis Gmelin, 1791

C. helvola L., 1758

C. lynx L., 1758

C. moneta L., 1758

C. vitellus L., 1758

C. clandestina passerina Melvill, 1888

Polinices mamilla L., 1758

Natica gualteriana Recluz, 1844

Malea pomum L., 1758

Tonna luteostoma Kuster, 1857

T. perdix L., 1758

Cymatium nicobaricum Roding, 1798

Naquetia triquetra Born, 1778

Chicoreus ramosus L., 1758

Volema paradisiaca Roding, 1798

Nassarius coronatus Bruguiere, 1789

N. distortus A. Adams, 1852

Pleuroploca trapezium L., 1758

Ancilla mauritiana Sowerby, 1830

Vasum rhinoceros Gmelin, 1791

V. turbinellus L., 1758

Harpa harpa L., 1758

Conus namocanus Hwass, 1792

C. augur Lightfoot, 1786

C. betulinus L., 1758

C. chaldeus Roding, 1798

C. coronatus Gmelin, 1791

C. ebraeus L., 1758

C. fulgetrum Sowerby, 1831

C. lividus Hwass, 1972

C. miles L., 1758

C. terebra thomasi Sowerby, 1881

C. tessulatus Born, l778

C. virgo L., 1758

Bulla ampulla L., 1758

Atys cylindricus Hebling, 1779

Melampus castaneus Muhlfield, 1815

Arca naviculularis Bruguiere, 1789

A. avellana Lamarck, 1819

Anadara antiquata L., 1758

A. uropygimelana Bory St Vincent, 1824

Barbatia amygdalumtostum Roding, 1798

B. velata Sowerby, 1843

Glycymeris petunculus L., 1758

Modiolus auriculatus Krauss, 1848

Brachidontes variabilis Krauss, 1848

Servatrina pectinata L., 1767

Pinctada radiata Leach, 1814

P. radiata f. nigra Gould, 1850

P. margaritifera L., 1758

Isognomon isognomon L., 1758

Chlamys senatoria Gmelin, 1791

Spondylus marisrubri Roding, 1798

Striostrea margaritacea Lamarck, 1819

Saccostrea cuccullata Born, 1778

Codakia punctata L., 1758

C. tigerina L., 1758

Ctena bella Conrad, 1837

Lucina victorialis Melvill, 1899

Wallucina erithraea Issel, 1869

Diplodonta genethila Melvill, 1898

Chama reflexa Reeve, 1846

Beguina gubernaculum Reeve, 1843

Bourdotia boschorum Dekker & Goud, 1994

Trachycardium flavum L., 1758

T. elongatum Bruguiere, 1789

Fragum fragum L., 1758

Mactra ovalina Lamarck, 1818

Atactodea glabrata Gmelin, 1791

Tellina staurelia Lamarck, 1818

T. palatum Iredale, 1929

T. claudia Melvil1 & Standen, 1907

Cadella semen Henley, 1845

Circe rugifera Lamarck, 1818

Asaphis violescens Forsskal, 1775

Gafrarium pectinatum L., 1758

G. tumidum Roding, 1798

Donax cuneatus L., 1758

Dosinia alta Dunker, 1848