Collecting in the surf

by Gavin Malcolm

Recently, I obtained a copy of Peter Dance’s Shell Collecting: An Illustrated History (1966), which gives an excellent historical perspective on shell collectors, natural history cabinets and voyages of discovery. I decided to follow some of the many references and surf the web looking for copies of some of the original publications. My focus was naturally towards Conus and Olividae, which I collect.

Recognition in science of species, subspecies, varieties and forms is governed by the code of the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) and the code has evolved with time. Today’s version can be found online at www.ICZN.org. It is founded on the binomial system introduced by Linnaeus in the tenth edition of System Naturae in 1758, whereby each valid name should consist of a genus and a species. In many original works, there is a short description in Latin, sometimes with a subdescription in the native language of the author.

Recognition in science of species, subspecies, varieties and forms is governed by the code of the International Commission of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) and the code has evolved with time. Today’s version can be found online at www.ICZN.org. It is founded on the binomial system introduced by Linnaeus in the tenth edition of System Naturae in 1758, whereby each valid name should consist of a genus and a species. In many original works, there is a short description in Latin, sometimes with a subdescription in the native language of the author.

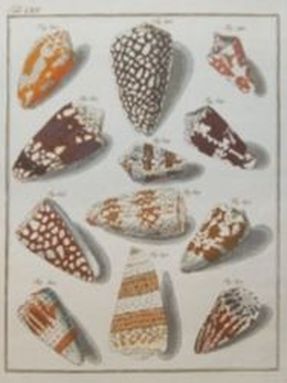

Before 1758, books were published using various ICZN-invalid systems for naming but many fine colour plates of shells in the cabinets of the wealthy were printed by authors such as Seba, D’Argenville, Gualtieri and Knorr (pictured above).

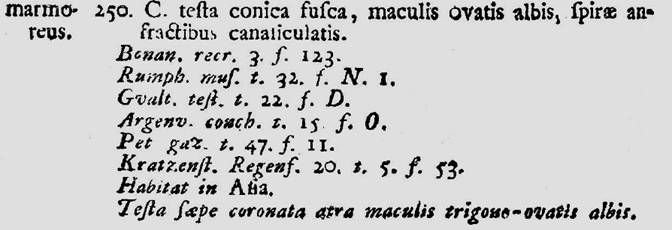

There are no figures in the works of the early authors who followed the valid Linnaean naming system, e.g. Linnaeus 1758, Born 1778 and Gmelin 1791. These works did not include plates or figures but referred to the previous publications by Knorr, Rumphius, etc. Here is an example from Linnaeus 1758: Conus marmoreus.

The text of Linnaeus lacks depth in the description of C. marmoreus and your Latin may be limited. But a picture speaks a thousand words and you can go to the AnimalBase website created by the university library of Göttingen in Germany, which is making available the great zoological works from 1600 to 1800, and download pages of the plates and text referenced by Linnaeus.

Here are two of the figures cited, in Regenfuss (left) and Gualtieri (centre), by Linnaeus in his description of C. marmoreus.

An author, in creating the description of a species, would normally study a group of specimens of the shell, the syntypes, and would select a specimen, the holotype, as representing the name being described. In many cases, these holotypes have been preserved in collections donated to museums. Current authors are expected to place the type specimens in the care of a major museum. In some cases, where a holotype was not selected by the original author, a later learned author can select a lectotype from the syntypes or may even select a figure (lectotype representative) in a publication which was referenced in the original description. In the case of C. marmoreus, Alan Kohn selected a specimen in the collection of the Linnean Society of London as the lectotype (see photo above, right). Kohn’s website (see below) and many museum websites now publish pictures of the types.

Communication in the early days was limited, so authors published descriptions creating duplicate names (homonyms) or published new names citing figures in plates previously used in different descriptions (objective synonyms). Authors did not have access to all the previous publications so they would describe new names which were later considered to be the same species as a previously described name. And so was born the world of subjective synonyms, where a later author, in publishing a review, uses judgement and documents these overlaps and duplicates as synonyms. At the last count, C. marmoreus had at least 10 synonyms.

Many descriptions found their way into literature through catalogues of the great collections which were created to show the wealth of their owners or to reference and describe specimens being sold. Lightfoot and Solander described the collection of the Duchess of Portland in 1786 in a sales catalogue and, in doing so, created 44 new cone names, many invalid, but six survive as accepted species today.

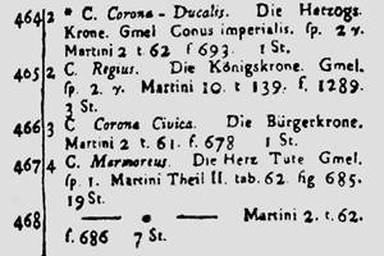

Roding described the collection of the Museum Boltenianum in 1798 (pictured below left) and created 123 new cone names, including many homonyms, but five species or subspecies are still recognised along with 58 synonyms.

Roding described the collection of the Museum Boltenianum in 1798 (pictured below left) and created 123 new cone names, including many homonyms, but five species or subspecies are still recognised along with 58 synonyms.

The ultimate shell book, covering every shell, has been an ambition of authors for many years and these books were released in editions similar to today’s magazines. An example is the Neues Systematisches Conchylien Cabinet published in Nuremberg by Martini from 1769. The works of Martini were continued by Chemnitz, Kuster, Weinkauff through to 1875 in various editions and publications. Shown here (below right) is the Martini plate quoted within the Museum Boltenianum catalogue for C. marmoreus (Plate 62, fig.685). The work did not use the binomial system and is considered an invalid source of new names, but many later authors referenced the excellent Martini figures in their publication of new descriptions.

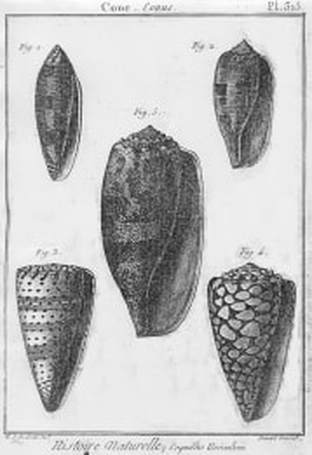

The French produced the Histoire Naturelle des Vers, part of the Encyclopédie Méthodique. It was started by Brugière, who used much of the Hwass collection for the cones, and this work was continued by Lamarck, Bory and Deshayes. You will find many of the plates of these publications for sale and pictured on the sites of reputable antique print dealers. Today, the shell collection of Hwass is in the Natural History Museum in Geneva.

The works of Lamarck are available on the web (see below left). The Encyclopédie Méthodique (Cones 1792) and its associated plates Tableau Encyclopédique (Cones 1798) are in the future plans of the AnimalBase website.

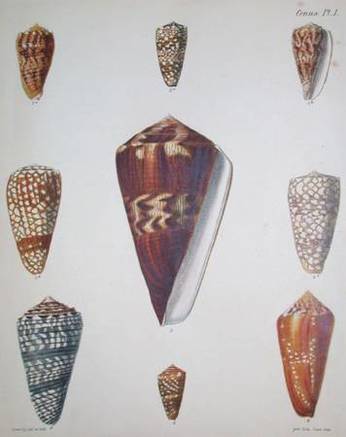

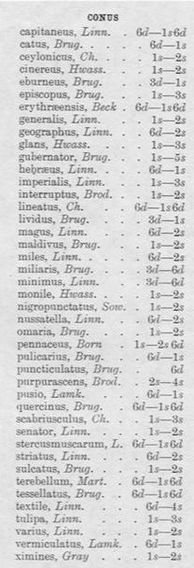

In London, the collection of Hugh Cuming provided thousands of specimens for Reeve and Sowerby to describe new species. The Sowerby family started with the Conchological Illustrations in 1833 and Thesaurus Conchyliorum in 1857. These kept three generations going with updates and releases covering more and more species. The Sowerby family were all skilled lithographers, conchologists and latterly dealers. Sowerby’s 1913 catalogue (right) shows prices slightly cheaper than those at the BSCC Shell Show today!

Sadly, the Sowerby works are difficult to find on the web but a visit to the French website Gallica will reveal a version of the Conchological Illustrations and the complete Thesauraus. Gallica was developed in 1995 to give the public access to the great classic books and provides easy download of the full text versions albeit the plates are in black and white. For those of you who remember your school French, a search (recherche) under the subjects (sujets) “coquillages” or “mollusques” should reveal the hundred or so shell books available. There is a health warning, however: the file sizes are large and are best tackled by broadband. Surprisingly, this site is the best source of original publications describing British fauna and you will find Jeffery’s British Conchology of 1862, Sowerby’s British Illustrations of 1887 together with Forbes and Hanley 1853 and Thomas Brown 1827 … yes, in English.

Sadly, the Sowerby works are difficult to find on the web but a visit to the French website Gallica will reveal a version of the Conchological Illustrations and the complete Thesauraus. Gallica was developed in 1995 to give the public access to the great classic books and provides easy download of the full text versions albeit the plates are in black and white. For those of you who remember your school French, a search (recherche) under the subjects (sujets) “coquillages” or “mollusques” should reveal the hundred or so shell books available. There is a health warning, however: the file sizes are large and are best tackled by broadband. Surprisingly, this site is the best source of original publications describing British fauna and you will find Jeffery’s British Conchology of 1862, Sowerby’s British Illustrations of 1887 together with Forbes and Hanley 1853 and Thomas Brown 1827 … yes, in English.

For those of you who collect and enjoy Conus then the excellent Conus Biodiversity website being developed by Alan Kohn is now available. Alan has gathered many of the original Conus descriptions, together with pictures of the type specimens from the museums around the world. You can download the original descriptions, many of which have the original colour plates including Reeve 1845.

Copyright law allows public availability of material more than 75 years old so the content is focused on 1758 to 1930. Also on offer for download is a spreadsheet database of all cones named, both extant and fossil. If you seek a description written after 1930 then you may have to go to a natural history museum library, most of which allow you to copy one article from any publication for study or scientific use.

Alan Kohn’s website is testing the modern concept of making e-books and scientific databases available to all and is introducing video clips and DNA-sequencing information about the species. Useful for the scientist, but I think, however, I will continue to use shell patterns and pictures for identification at the Shell Show.

This article by Gavin Malcolm was first published in our magazine Pallidula in October 2006.