Collecting in Japan

by John and Jenny Whicher

Photography by John Whicher

Photography by John Whicher

While Japan might not seem the obvious destination for a shelling holiday: think again. Flights are competitive and the economy has still not recovered from the Asian financial collapse of 10 years ago, so it is no more expensive than the UK. Car hire is reasonable and all hire cars have a built in GPS, so click the cursor on your chosen beach and follow the red line! There is virtually no crime and everyone you meet is very helpful whether they speak English or not. Almost anything from the sea is on the menu so many different types of shell are on sale in fish shops and restaurants. We bought Buccinum tsubai Kuroda, 1953 and Omphalinus Pfeiffer Dunker, 1844 at food counters in Kyoto, cooked them in the kettle provided in the hotel room, and ate them as snacks.

Our first destination was the Noto-Hanto Peninsula, chosen from the description in the Lonely Planet Guide as an unspoilt rural area not touched by modern Japan, comprising a rugged hilly interior with a coastline studded with sleepy little fishing villages – it sounded good for shells. The peninsula juts into the Japan Sea on the north side of the main island, Honshu. Its western coast is rocky and spectacular, battered by rough seas and prevailing winds. The east coast is quiet with shallow seas and deep inlets. The Japanese coast takes a bit of getting used to as more than 80% of it is covered with concrete sea walls or protected by sea defences of one sort or another. At first we were concerned that this might have eliminated good collecting grounds but the reverse was the case. Behind the defences there are protected areas in which shells are trapped and pile up in large numbers. A good example was the very first place we stopped south of Nanao on the east side of the peninsula, where we found piles of Babylonia japonica Reeve, 1842 and Anadara subcrenata, Lischke 1869, many worn and broken but among them good specimens. Further along this coast we found a succession of small fishing villages inhabited by Glycymeris albolineata Lischke, 1872, Lunella cinerea Born, 1778 and Turbo cornutus Lightfoot, 1786 on the shallow mud flats. Wajima, the main town, has a fascinating morning market where all sorts of fish are on sale including piles of Turbo cornuta and Haliotis gigantea Gmelin, 1791. The latter are eaten smoked. The rocky west coast is very different and we collected in the pouring rain, lashed by strong winds and surf. However in one rocky cove we found a profusion of broken Pomaulax japonicus Dunker, 1844, some the size of dinner plates! We did, however, collect some smaller specimens together with a fine selection of different species of Gibbula. At the south west extremity of the peninsula, late in the afternoon we came upon a strange little fishing harbour off the shore and accessible only on the low tide. Here we stumbled upon Nirvana.... The Japanese are very neat and tidy and the cleanings from the nets tend to be piled in one or two places in each harbour.

The first pile we found had been burnt because, as we later discovered, the nets catch huge amounts of polythene bags and bottles as well as shells. From the edges of the fire we collected Cancellaria spengleriana Deshayes, 1830, Ceratostoma burnetti Adams & Reeve, 1849, Cryptonatica janthostomoides Kuroda & Babe, 1961, Doxander japonicus Reeve, 1851, Fulgoraria rupestris Gmelin, 1791, Fusinus longicaudus Lamark, 1810, Fusinus perplexus A. Adams, 1864, Fusitriton oregonensis Redfield, 1848, Glassaulax didyma Roding, 1798, Hemifusus tuba Gmelin, 1791, Kelletia lischkei Kuroda, 1953, Phalium bisulcata Schubert & Wagner, 1829, Pteropurpura adunca Sowerby, 1834 and Tugurium exutum Reeve, 1843; unfortunately there were several large specimens of Hemifusus colosseus Lamarck, 1816 charred beyond hope. The rain drove Jenny back to the car but I decided to search the remainder of the jetty and just as I was turning back I found a huge pile of Cancellaria nodulifera Sowerby, 1825, Fusinus perplexus A. Adams 1864, Phalium bisulcata Schubert & Wagner, 1829 and Glassaulax didyma Roding, 1798. I collected as many as I could carry but left many behind. This was certainly some of the best collecting I have ever known and with more time I have no doubt that the many other small harbours along this coast would have produced similar rewards.

Phalium bisulcatum Schubert & Wagner, 1829

Our next collecting stop was nearly a thousand kilometres away in the south of Kyushu, Japan's most southerly island. Here on a small spit of sand we saw a wonderful spread of Umbonium costatum Kiener, 1834 and Umbonium moniliferum Lamarck, 1810. Other beaches in this area yielded a wide range of shells. Returning up the west coast of Kyushu we wanted to visit the fishing town of Minimata, somewhat of a pilgrimage for anyone interested in environmental medicine. In the mid-1950s, fishermen living around the bay began suffering from a mysterious disease. The illness attacked the nervous system, causing convulsions, tremors, loss of speech and hearing, often severe mental disability, madness and an agonising death. The first case of what came to be known as Minimata disease was officially diagnosed in 1956, but it took another three years to identify the cause as organic mercury poisoning. A little surprising in view of the classical symptoms, well known in the last century amongst felt workers making hats using mercury salts, hence the expressions "hatters shakes" and the better known "mad as a hatter" popularised in the Mad Hatter in Alice in Wonderland. Tragically it was nearly another decade before Chisso, a local chemical company, stopped pumping their mercury-laden waste into the sea. The victims battled for years against the local authorities, the company and the national government to win recognition of their suffering and adequate compensation. Eventually, a number of families took the company to court in 1969, by which time a nationwide support movement had evolved. Four years later, Chisso was finally judged liable – too late for many, of course. To date, although the government recently declared the bay mercury-free, nearly 2,000 people have died of Minamata disease, while around 13,000 have been certified as afflicted. Though the true extent of the tragedy will never be known, some estimates put the total number of people affected as high as 100,000.

Of course the victims consumed the mercury in fish but most particularly shellfish such as the abundant and widely eaten Anodontia edentula Linné, 1758. So it was with some sadness that we plodded onto the mudflats at low tide and collected Anodontia edentula Linné, 1758, Circe scripta Linné, 1758, Dosinia japonica Reeve, 1850 and Lunella coronata Gmelin, 1791.

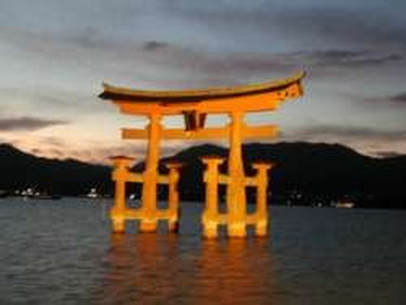

Finally we stayed on the famous island of Miya-jima in the inland sea, across a strait from Hiroshima. Here is the famous gate and temple set in the sea (or sand at low tide). Said to be the best view in Japan and certainly enhanced by the layer of pretty Tapes platyptycha Pilsbry, 1905 crunching underfoot at every step. Oysters are farmed on floats in the shallow water and this is the home of the "Ravenous Voyager" Rapana venosa Valenciennes, 1846, which abounds here and is served in local restaurants "in the shell" on a bed of hot charcoal (thus ruining the shell) with soya sauce. Having lunched on this local delicacy I was presented with a splendid large (undamaged) specimen by the waitress after some difficulty in explaining what I wanted. The oysters were also delicious cooked in the same way. At the local harbour we found a pile of fine Turbo cornutus Lightfoot, 1786 of a completely spine-free variety.

There is no doubt that Japan has a huge potential for shell collecting. The coastline stretches from the coast of Siberia to the tropical islands of the Okinawa group and there are many endemic species. We had very little time and collected almost no live specimens but you could easily do so. Japan has a poor record for conservation and as far as we could tell there are no restrictions on collecting, in fact far from it, as the Japanese collect so many different marine organisms for food.

This article by John and Jenny Whicher was first published in our magazine Pallidula in April 2003.

Species list

Anadara subcrenata Lischke, 1869

Anodontia edentula Linne, 1758

Architectonica maxima Philippi, 1849

Babylonia japonica Reeve, 1842

Barbatia cometa Reeve, 1843

Barbatia virescens Reeve, 1843

Batillaria zonalis Brugiere, 1792

Buccinum tsubai Kuroda, 1953

Caecella chinensis Deshayes, 1855

Cancellaria nodulifera Sowerby, 1825

Cancellaria spengleriana Deshayes, 1830

Cantharus cecillei Philippi, 1844

Cantharus undosa Linne, 1758

Cellana nigrolineata Reeve, 1857

Ceratostoma burnetti Adams & Reeve, 1849

Chlorostoma lischkei Tapparoni-Canefri, 1874

Chlorostoma turbinatum A. Adams, 1853

Chlorostoma xanthostigma A. Adams, 1852

Circe scripta Linne, 1758

Conus orbignyi Audouin, 1831

Crassostrea gigas Thurnberg, 1793

Cryptonatica janthostomoides Kuroda & Habe, 1961

Cymatium parthenopeum von Salis, 1793

Cypraea gracilis Gaskoin, 1839

Dolmena marginata Sowerby, 1874

Dosinia japonica Reeve, 1850

Doxanda japonicus Reeve, 1851

Ficus subintermedia Orbigny, 1852

Fulgoraria rupestris Gmelin, 1791

Fusinus longicaudus Lamark, 1810

Fusinus perplexus A. Adams, 1864

Fusitriton oregonensis Redfield, 1848

Gafrarium divaricatum Gmelin, 1791

Glassaulax didyma Roding, 1791

Glycymeris albolineata Lischke, 1872

Granata lyrata Pilsbry, 1905

Haliotis gigantea Gmelin, 1791

Hemifusus tuba Gmelin, 1791

Kelletia lischkei Kuroda, 1953

Littorina brevicula Philippi, 1844

Lunella cinerea Born, 1778

Lunella corona Gmelin, 1791

Macoma sectior Oyama, 1950

Modiolus difficilis Kuroda & Habe, 1961

Monodonta labio Linne, 1758

Monodonta neritoides Philippi, 1844

Nerita albicilla Linné, 1758

Niotha livescens Philippi, 1844

Nipponacmea schrenki Menke, 1851

Notoacmea concinna Teramachi

Novathaca schenki Nomura, 1937

Nuttallia olivacea Jay, 1857

Oliva mustelina Lamark, 1810

Omphalinus nigerrimus Gmelin, 1791

Omphalinus pfeifferi Dunker, 1844

Omphalinus rusticus Gmelin, 1791

Paphia euglypta Philippi, 1847

Patinopecten yessoenensis Jay, 1857

Phalium bisulcatum Schubert & Wagner, 1829

Phalium flammiferum Roding, 1790

Pholadidea kamakurensis Yokoyama, 1922

Phos senticosus Linné, 1758

Pollia mollis Gould, 1860

Pomaulax japonicus Dunker, 1844

Pteropurpura adunca Sowerby, 1834

Purpura panama Roding, 1798

Rapanavenosa Valenciennes, 1846

Saxidomus purpuratus Sowerby, 1857

Siphonalia cassidarieformis Reeve, 1843

Thais bronni Dunker, 1844

Thais clavigera Küster, 1860

Thais luteostoma Holten, 1803

Trochus maculatus Linne, 1758

Trochus sacellus Dunker, 1844

Tugurium exutum Reeve, 1843

Umbonium costatum Kiener, 1834

Umbonium moniliferum Lamarck, 1810

Anadara subcrenata Lischke, 1869

Anodontia edentula Linne, 1758

Architectonica maxima Philippi, 1849

Babylonia japonica Reeve, 1842

Barbatia cometa Reeve, 1843

Barbatia virescens Reeve, 1843

Batillaria zonalis Brugiere, 1792

Buccinum tsubai Kuroda, 1953

Caecella chinensis Deshayes, 1855

Cancellaria nodulifera Sowerby, 1825

Cancellaria spengleriana Deshayes, 1830

Cantharus cecillei Philippi, 1844

Cantharus undosa Linne, 1758

Cellana nigrolineata Reeve, 1857

Ceratostoma burnetti Adams & Reeve, 1849

Chlorostoma lischkei Tapparoni-Canefri, 1874

Chlorostoma turbinatum A. Adams, 1853

Chlorostoma xanthostigma A. Adams, 1852

Circe scripta Linne, 1758

Conus orbignyi Audouin, 1831

Crassostrea gigas Thurnberg, 1793

Cryptonatica janthostomoides Kuroda & Habe, 1961

Cymatium parthenopeum von Salis, 1793

Cypraea gracilis Gaskoin, 1839

Dolmena marginata Sowerby, 1874

Dosinia japonica Reeve, 1850

Doxanda japonicus Reeve, 1851

Ficus subintermedia Orbigny, 1852

Fulgoraria rupestris Gmelin, 1791

Fusinus longicaudus Lamark, 1810

Fusinus perplexus A. Adams, 1864

Fusitriton oregonensis Redfield, 1848

Gafrarium divaricatum Gmelin, 1791

Glassaulax didyma Roding, 1791

Glycymeris albolineata Lischke, 1872

Granata lyrata Pilsbry, 1905

Haliotis gigantea Gmelin, 1791

Hemifusus tuba Gmelin, 1791

Kelletia lischkei Kuroda, 1953

Littorina brevicula Philippi, 1844

Lunella cinerea Born, 1778

Lunella corona Gmelin, 1791

Macoma sectior Oyama, 1950

Modiolus difficilis Kuroda & Habe, 1961

Monodonta labio Linne, 1758

Monodonta neritoides Philippi, 1844

Nerita albicilla Linné, 1758

Niotha livescens Philippi, 1844

Nipponacmea schrenki Menke, 1851

Notoacmea concinna Teramachi

Novathaca schenki Nomura, 1937

Nuttallia olivacea Jay, 1857

Oliva mustelina Lamark, 1810

Omphalinus nigerrimus Gmelin, 1791

Omphalinus pfeifferi Dunker, 1844

Omphalinus rusticus Gmelin, 1791

Paphia euglypta Philippi, 1847

Patinopecten yessoenensis Jay, 1857

Phalium bisulcatum Schubert & Wagner, 1829

Phalium flammiferum Roding, 1790

Pholadidea kamakurensis Yokoyama, 1922

Phos senticosus Linné, 1758

Pollia mollis Gould, 1860

Pomaulax japonicus Dunker, 1844

Pteropurpura adunca Sowerby, 1834

Purpura panama Roding, 1798

Rapanavenosa Valenciennes, 1846

Saxidomus purpuratus Sowerby, 1857

Siphonalia cassidarieformis Reeve, 1843

Thais bronni Dunker, 1844

Thais clavigera Küster, 1860

Thais luteostoma Holten, 1803

Trochus maculatus Linne, 1758

Trochus sacellus Dunker, 1844

Tugurium exutum Reeve, 1843

Umbonium costatum Kiener, 1834

Umbonium moniliferum Lamarck, 1810