Haliotidae: the Simon Taylor Collection

by Simon Taylor

Photography by Simon Taylor

Photography by Simon Taylor

Like so many other collectors, my childhood curiosity with natural history was strongly influenced by visits to seaside shell shops – most notably, in my case, that in Brixham, South Devon. My purchases made there were lovingly placed in a small display alongside self-collected seashell specimens from sites local to me in Essex such as Mersea Island and Walton-on-the-Naze. The fascination with shells was further developed by receiving a copy of Gert Lindner's wonderful little book Seashells of the World for my twelfth birthday. Since then I have amassed several thousand shells from all over the world.

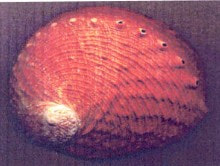

A specific interest in the Haliotidae (abalones, ormers, sea ears – call them what you will) was stirred by the gift of a Haliotis tuberculata coccinea Reeve, 1846 from a relative who had visited the Canary Islands. This was a super little specimen with perfect interior nacre. The discovery of Ken Wye's old shop in Manette Street resulted in further acquisitions, notably a gorgeous, near gem, H. rubra Leach, 1814, and that was it: I was hooked.

The attraction is many-fold: the row of holes (often referred to as tremata) is almost unique amongst modern gastropods and, of course, the shells' pearly interiors are outstanding (these are among the traits which mark the family as phylogenetically primitive and hence generally to be found near the front of shell books!). However, many Haliotids can have extraordinarily attractive external colouration and delicate, almost satin-textured sculpture. The family has only approximately 60 accepted valid species, but is hugely variable, for example from the small (~20mm), delicate yet colourful beauty of H. pulcherrima Gmelin, 1791 or H. jacnensis Reeve, 1791 to the hulking, eroded, monsters (300mm+) of H. rufescens Swainson, 1822. This makes species relatively easy to recognise, with a few notable exceptions and some confusing juveniles. Some species are known to hybridise and I have an example of H. rufescens x sorenseni and also a delightful "intergrade" between H. brazieri Angas, 1869 and H. hargravesi Cox, 1869.

The family is widely distributed, with species-rich areas on the west coast of North America, in the waters around Australia, and through the tropical Indo-Pacific to Japan. The majority of species inhabit the sublittoral zone and the family's fossil record (they are first recorded in the Upper Cretaceous) tends to indicate that this has always been the case.

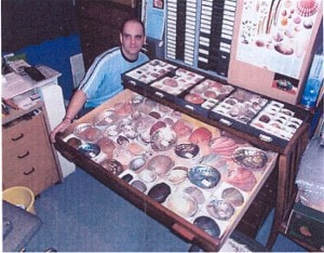

Over the years I have collected several hundred specimens, representing most species, though there are still a few "holy grails" left which are extremely rare, inhabit deeper water and are thus difficult to come by. These include the classic Haliotis rarity, H. pourtalesii Dall, 1881, from in and around the Caribbean, plus the Brazilian H. aurantium Simone, 1998, H. dalli Henderson 1915 from the Galapagos and H. roberti McLean, 1970 from Cocos Island, Costa Rica (if anybody out there has specimens of these or other rare/unusual Haliotis for sale or exchange, please get in touch.)

The family has generally had a somewhat unfashionable reputation within shell-collecting circles, but seems recently to have gained in popularity, particularly with European collectors. An American, Dr Daniel L. Geiger, has produced lots of work on the family over the last eight years or so, doing much (but not all) to sort out what was a rather confused nomenclature and drawing interest and attention with some well-illustrated publications. Also recently, new species have been described of which some, if not all, appear to be valid.

Further research has been conducted as a result of the abalone aquaculture industry, where the animals are farmed for their meat. Larger species have always been an important human food resource where available, including the European ormer, H. tuberculata L. 1758, and in many places collection from the wild has had to be strictly controlled or stopped to protect stocks. Aquaculture has met the demand for meat, with the spin-off that Haliotis biology has been studied very closely indeed to maximise yields, etc. Haliotis have also proved ideal for genetic studies, which have helped the work of Dr Geiger.

My interest in Haliotis has been nurtured and enhanced by numerous people, but none more so than Thora Whitehead of Brisbane, Australia, with whom I have been corresponding since my teens (I am now 35) and who has proved an endless inspiration. Another great help has been my membership of the British Shell Collectors' Club: I have been a member for around ten years now and attend all the events I can. Members are welcoming, friendly, helpful and very knowledgeable and the events are great opportunities to chat, learn and, of course, to buy or exchange shells.

Inevitably, it is getting harder and harder to find specimens of Haliotidae that will add to the collection's variety and so I am now looking more closely at other families, such as Trochidae, Turbinidae, Strombidae and Volutidae and bivalves. I also enjoy collecting British shells and fossils, especially those from the East Anglian crag deposits. However, there will never be a family closer to my heart than the Haliotidae.

This article by Simon Taylor was first published in our magazine Pallidula in April 2003.