Spotlight on fossil Cypraeidae: the J. Joseph Collection

by Julian Joseph

Photography by Julian Joseph

Photography by Julian Joseph

I have been collecting shells for longer than I care to remember. Like most, I started with a general collection, but after a few years I began to restrict myself to a small number of families – Conidae, Volutidae, Muricidae and a few others. Eventually I specialised in a single family, the family loved more than any other, Cypraeidae – the cowries. Most cowry connoisseurs inevitably discover that they can collect a large number of the species and forms, but it is well-nigh impossible to acquire those last few, elusive species and obscure, excessively rare forms. Even if, like me, one is prepared to accept dead-collected specimens so eroded and bleached as to be barely recognisable, it is probably safe to say that one can never have a complete collection of this family.

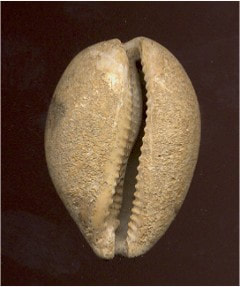

Notoluponia murraviana(Tate, 1890): base

When I was studying zoology as an undergraduate in London many, many years ago, I decided (much to my tutor's disapproval) to do my six-week undergraduate research project on the evolution of the Cypraeidae. To do this I spent two or three delightful weeks studying the collections of fossil Cypraeids at the Natural History Museum in South Kensington. This inspired in me an interest in a whole new world of extinct cowries whose existence is quite unknown to the majority of shell collectors: huge, 8–12 inch tuberculate Gisortia of France, strange Umbilia with extraordinarily long siphonal canals, and Notoluponia, which link the South African Luponia with Notypreaea in Australia.

The cowries are believed to have evolved from a family of smallish, vaguely Marginella-like shells called the Collumbellinidae, specifically, from the genus Zittellia Gemellaro, 1870. These lived during the Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous periods, about 110–150 million years ago, and were members of the superfamily Strombacea, which includes the modern Strombidae. This gave rise to the Cypraeidae, the Ovulidae (Amphiperatidae) the Triviidae (Eratoidae) and a few very small families. The first known true cowries belonged a genus of small, fairly ordinary-looking Cypraeids with a prominent spire and short, fine teeth called Palaeocypraea during the upper Cretaceous period, some 100 million years ago. Fossils of these have been found in Europe, though I have yet to get any myself. At around the same time lived another important genus, Bernaya. This genus is known to collectors through the "living fossil" B. teulerei (Cazenavette, 1846). This genus is believed to have given rise to the modern subfamilies Bernayinae (which also includes the South African Barycypraea fultoni Sowerby, 1903, the South American Siphocypraea mus (Linné, 1758) and the Zoila of Australia) and the Cypraeinae. The other major branches of the cowry family, the Erroneinae, probably developed directly from Palaeocypraea.

Unfortunately fossil Cypraeidae are, with very few exceptions, difficult to acquire. Two species are common in Florida: Siphocypraea problematica Heilprin, 1887 and S. carolinensis (Conrad, 1841). S. problematica is notable for a strange, very deep slit around the spire. Both are extremely variable, and many of the related species may well turn out to be synonyms. I have a specimen of S. hertweckorum Petuch, 1991 which still has a rich brown colour and full gloss, and looks almost like a live-taken shell, despite being at least 3 million years old. These common species are sometimes available from dealers, as, occasionally, are a few European species. Although the Mediterranean coast of Europe is now home to only three cowry species, during the Miocene period about 10–20 million years ago there was a rich fauna, with many species of Schilderia (only one species, S. achatidea (Sowerby, 1937), now survives), Zonaria, Lyncina and Trona. Very few books on shell collecting cover fossil species, Felix Lorenz's Guide to Worldwide Cowries and his Monograph of the Living Zoila being welcome and very useful exceptions. The malacologist Franz Schilder, who was active in the middle third of the 20th century, wrote many papers on fossil as well as living cowries. These are perhaps the most useful references for identification purposes. Unfortunately many are not in English, so I translated several of them for ease of reference.

|

Cypraeorbis willcoxi

(Dall, 1890): dorsum |

Cypraeorbis willcoxi

(Dall, 1890): base |

So what of my own collection? Over a period of about twenty years I have managed to amass a grand total of 48 species and forms. The majority are from Florida and Europe, but I have a few from Australia and East Africa. Many of the European and African shells are somewhat eroded, resembling beached shells. On the other hand I have a specimen of Cypraeorbis willcoxi (Dall, 1890) from the Miocene of Florida (perhaps as much as 16 million years old) which looks like an Erosaria turdus (Lamarck, 1810) with golden speckling and gloss (no relation, of course!). This one is doubly exciting because Cypraeorbis is a very ancient genus, many species being known only from internal casts. But my favourites are the Australian species. These don't have any colour left, but they do have a little gloss, and are in quite decent condition considering they are over 5 million years old. My Umbilia sphaerodoma (Sowerby, 1845) looks quite similar to its modern relatives U. capricornica Lorenz, 1989 and U. hesitata (Iredale, 1916) apart from its very extended extremities, with strange tubercles anteriorly. The narrow aperture and incredibly long labial teeth set it apart from any of its living relatives, though. The Notoluponia species are fascinating, and do indeed look like a hybrid between Luponia edentula (Gray, 1825) and some of the Notocypraea species that now inhabit Australian waters. It is unfortunate they are so fragile, one of them having fallen to pieces for no apparent reason a few years ago. I have a fossil specimen of Austrocypraea reevei (Sowerby, 1832) to compare with Recent specimens, and a number of other fossil Austrocypraea, the best known of which is A. contusa (McCoy, 1877), so called because it looks as if it is covered in contusions as a result of some nasty injury. A. reevei also shows this characteristic, but not as strikingly.

Collecting fossil cowries is certainly not an easy means of acquiring additional species, but it is extremely rewarding to discover a well-preserved cowry which is several million years old. There is much yet to be learned, and they hold one of the keys to understanding the complex relationships between the species living today.

References

Lorenz, F. and Hubert, A. (2000), A Guide to Worldwide Cowries (ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany)

Lorenz, F. (2001), Monograph of the Living Zoila (ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany)

Schilder, F.A. (1931), "Les Cypraeaceae fossiles des Bouches-du-Rhone", Annales du Musée d'histoire naturelle de Marseille, 24: 87–90

Schilder, F.A. (1932), "Revisione delle Cypraeacea del Piemonte e della Liguria", Rivista Italiana di Palaeontologia, 38: 9–52

Schilder, F.A. (1935), "Revision of the Tertiary Cypraeacea of Australia and Tasmania", Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 21/6: 325–55

Wenz, W. (1940), "Superfamilia Cypraeacea" in Handbuch der Paläozoologie, 6, Gastropoda, 1/4 (Gebruder Borntraeger: Berlin): 949–1014

Lorenz, F. and Hubert, A. (2000), A Guide to Worldwide Cowries (ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany)

Lorenz, F. (2001), Monograph of the Living Zoila (ConchBooks: Hackenheim, Germany)

Schilder, F.A. (1931), "Les Cypraeaceae fossiles des Bouches-du-Rhone", Annales du Musée d'histoire naturelle de Marseille, 24: 87–90

Schilder, F.A. (1932), "Revisione delle Cypraeacea del Piemonte e della Liguria", Rivista Italiana di Palaeontologia, 38: 9–52

Schilder, F.A. (1935), "Revision of the Tertiary Cypraeacea of Australia and Tasmania", Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 21/6: 325–55

Wenz, W. (1940), "Superfamilia Cypraeacea" in Handbuch der Paläozoologie, 6, Gastropoda, 1/4 (Gebruder Borntraeger: Berlin): 949–1014

This article by Julian Joseph was first published in our magazine Pallidula in April 2002.